At first glance, a salad may just seem like a bowl of vegetables, but in reality it goes much deeper than that. There’s a lot of planning, preparation, input and maintenance that has to happen before the salad bowl hits the table.

World Food Day, celebrated this year on October 16, is devoted to promoting nutritious diets and food security for all. Nutrition is an continuous cycle. Plants depend on nitrogen (N) and other macro- and micronutrients to provide them with the nutrition they need to start and stay strong. In turn, those crops make the journey from the field to the dinner table where they provide us with the nutrition we need to survive and produce more crops. The cycle begins and continues again and again. As the world’s population continues to grow, it becomes more important for farmers to discover ways to produce more from the same amount of land, and in an efficient manner.

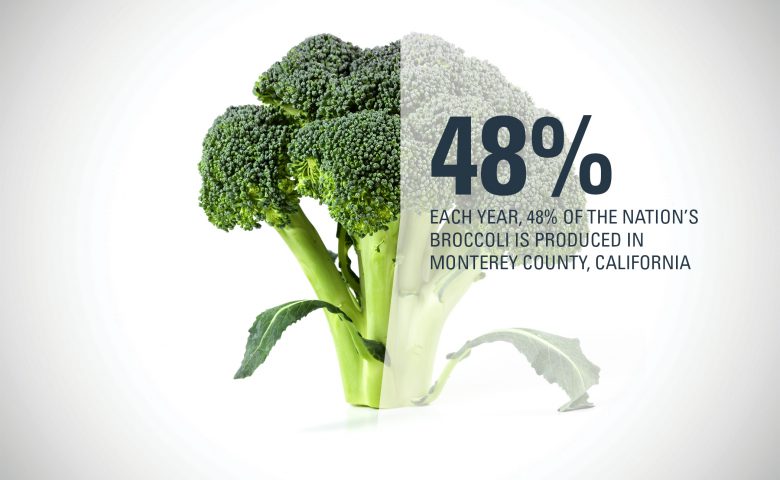

The Salinas Valley of California’s Monterey County is home to a climate much like that of the Mediterranean, making it an ideal location for producing a large variety of crops that wind up on our dinner tables.

Salinas Valley is home to around 370,000 acres of crops like strawberries, lettuce, tomatoes, spinach, broccoli, cauliflower, wine grapes, and celery.

Out of that, around 744,000,000 pounds of fruits and vegetables are exported to other countries each year. This area has been appropriately dubbed the “Salad Bowl of the World.”

Lettuces and Leafy Greens – The Key Component

No tossed salad is complete without a leafy green foundation – whether that be a variety of lettuces, spinach, kale or arugula. Greens provide the platform for all other elements of the salad and bring it all together in flavorful, healthy harmony. But before our lettuce makes it to the salad bowl, these crops crave vital macro and micronutrients needed for their own health and performance.

The nitrogen demand for lettuces is highest during the month before harvest, when about 70-80 percent of the crop’s total nitrogen is taken up. Because of this, pre-plant nitrogen application needs for lettuce are usually low, with the exception of years where rates of leaching are high. Later in the season, lettuces require an application ranging anywhere from 100 to 180 pounds, depending on nitrogen availability in the soil and the season during which the crop is being grown.

Spinach is susceptible to leaching by winter rains, so fall applications of nitrogen are not typically recommended. Pre-plant nitrogen application consists of about 20 pounds of nitrogen per acre. An additional 20 to 30 pounds of nitrogen are applied via top-dress or water-run application in season.

Strawberries – A Sweet Addition

Fruits such as strawberries often are the perfect complement to a savory salad. A strawberry plant’s nitrogen uptake rate is slow through the winter. To minimize the risk of leaching, an application of around 150 pounds of controlled release fertilizer per acre before planting helps ensure young plants get off to a strong start. It’s also important to apply a small dose of N-P-K soluble fertilizer a week or two before transplant.

The remainder of the strawberry plant’s nitrogen needs is fertigated throughout the growing season. Split applications of nitrogen in strawberries have been found to produce higher yields compared to applying all up front prior to planting. 150 to 200 pounds per acre of nitrogen is shown to be sufficient.

These are obviously just a few of the many crops that could potentially end up in your salad bowl, not to mention just a handful of the crops grown in the Salinas Valley, but it’s important to take a step back and think about what it takes to produce the food we eat every day.

Tomatoes – A Juicy Garnish

A salad is just a bowl of lettuce without the right toppings. Ripe, juicy tomatoes are the perfect addition to any tossed salad. Tomatoes are grown for a specific market. For instance, fresh market tomatoes are intended to be sold as produced, whereas processing tomatoes will be made into tomato products like sauces and soup. Like lettuces, tomatoes take up most of their nitrogen later in the growing season, leaving a lot of those nutrients vulnerable to loss.

Because of this, agronomists and pest control advisers (PCAs) suggested that pre-plant applications should be limited to 5-15 pounds per acre. Fertigation is the preferred method of nitrogen delivery for this crop. Tomatoes that are irrigated using drip irrigation should receive about 175 pounds of nitrogen per acre. If fertigation is used, no foliar application is typically needed.

Cauliflower and Broccoli – For Added Crunch

To continue with the theme of salad toppings, let’s move on to the cruciferous vegetables often included in a tossed salad – broccoli and cauliflower. These vegetables crave N and demand more of it throughout the growing season that many other crops. A crop of cauliflower requires about 200 pounds of nitrogen per acre – 40 of which is applied at planting. The rest is applied over one to three sidedress application during the period of the season before head formation. Any nitrogen applied after heading could cause leafy or loose curds, which is not ideal for marketing this crop.

Like cauliflower, broccoli also requires about 200 pounds of nitrogen per acre to produce 90 percent of its maximum yield. However, it’s important to note that it takes an additional 200 pounds per acre to reach maximum yield potential – that’s an additional 10 percent gain, but most farmers would not be likely to invest the additional cost for a minimal gain.

These are obviously just a few of the many crops that could potentially end up in your salad bowl, not to mention just a handful of the crops grown in the Salinas Valley. But it’s important to take a step back and think about what it takes to produce the food we eat every day.